Views expressed in opinion columns are the author’s own.

If you attend the University of Maryland, you probably remember your phone blowing up with alerts about the stabbing and subsequent death of Richard Collins III. Sean Urbanski, a white student at this university, was charged with murder in the stabbing. The death of Collins, who was black, is being investigated as a possible hate crime. Collins was set to graduate the following week and was a newly commissioned second lieutenant in the Army.

This was a wake-up call for many of us: Hate is alive and close to home. But while Urbanski’s mugshot is emblazoned in our minds, we should not ignore that others charged with the murders of black men and women are being acquitted left and right. Police brutality against black men and women and hate crimes come from the same source: prejudice and hate. It is unlikely that any officers have prior intention of murder, but if an officer finds it easier to shoot at a black citizen than a white one, then we must treat these as murders and more than simply unavoidable tragedies.

On June 16, Jeronimo Yanez, the Minnesota police officer responsible for the death of Philando Castile last year, was acquitted of manslaughter and other charges. In recently released footage, Yanez, who pulled over Castile for a traffic violation, can be seen shooting Castile after Castile reached for his wallet. Castile willingly disclosed that he had a firearm and told Yanez that he was not reaching for it. Yet he was killed in front of his girlfriend and her four-year-old daughter. The city offered Yanez a “voluntary separation” from the police department so he can find another job. A helpless black victim and an exonerated killer is a trope that hails back to the days of lynching. We cannot look back with horror on those crimes from the past but allow ones like these.

On June 20, Charleena Lyles, a pregnant mother of four, was shot to death by two police officers. She had called them to report a burglary. Lyles had been living in housing provided by Solid Ground, an organization providing services and long-term housing to women and families facing homelessness in Seattle. Lyles suffered from mental health issues, and the police knew. The police report says she brandished a knife, but it is unknown whether she threatened them. The police did not use a taser before fatally shooting her. The police did not take the proper measures, despite knowing that Lyles had mental health struggles and being called by Lyles herself.

So far, 2017 has been the worst year on record for deaths by police brutality. Police officers have killed more than 600 people this year. In May, three victims were 15-year-old black boys, including Jayson Negron. When Connecticut police shot and killed Negron on May 9, he did not die instantly. He lay on the ground and bled out on the sidewalk. He did not receive the necessary medical attention for about six hours. Jayson, like many victims of police violence, was not a threat. He was a young boy who needed help and got none. He was a black boy who was neglected by this country’s legal system.

Racially motivated or influenced violence has taken many forms throughout our nation’s history, from police brutality and modern hate crimes to lynching, a form of extralegal punishment that reached its peak in the late 19th century. We know now that many of the supposed “crimes” committed by black lynching victims were largely exaggerated or completely made up. Lynching was not justice at all. It was a thinly veiled way to decimate the black community.

Today, we treat police brutality as an occupational hazard, a circumstantial loss or even simply a shame. But these modern lynchings exist just like they did a hundred years ago. Worse, police officers are the people set to protect the public. The lack of a conviction in these cases sends the message that it is more of a crime to be a black person than to kill a black person.

Of course, many officers have minds unclouded by internalized fear, and these officers excel in an incredibly difficult career. I have the utmost respect for police officers who treat all citizens equally and fairly and conduct themselves as their job requires. But far too many of them fall short of this standard. Only an absolutely broken criminal justice system could strike fear into citizens it aims to serve. We should not settle for a system like this.

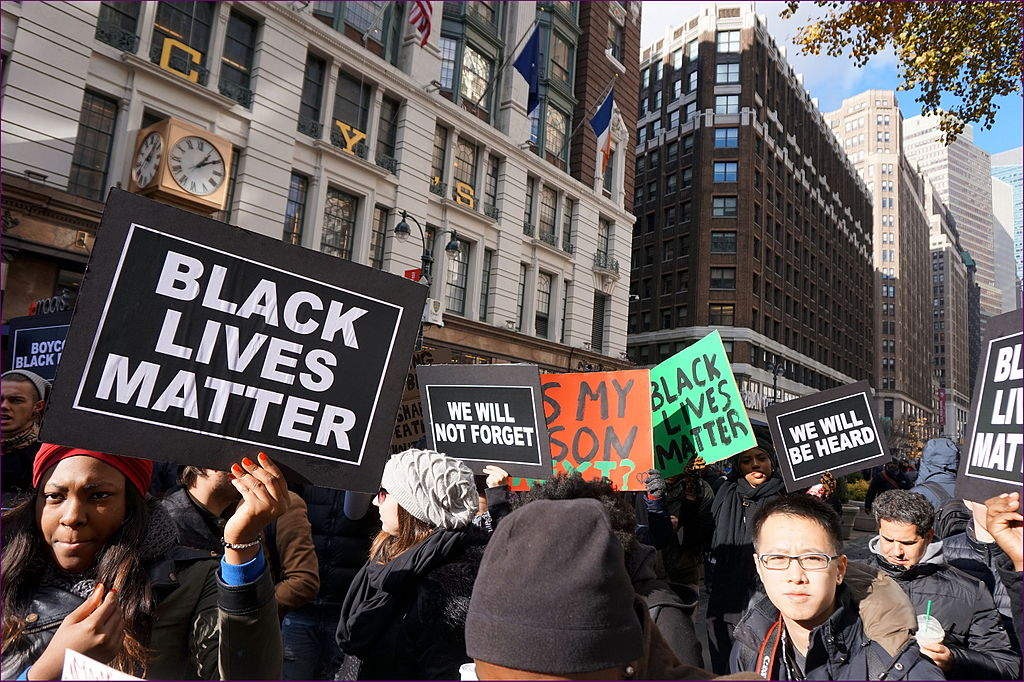

We have watched #BlackLivesMatter go from a grassroots movement to a national call to action. And maybe some of us have lost the sense of urgency that victims like Castile, Lyles and Negron needed us to feel. We cannot sink into institutionalized numbness, and we cannot let the sheer numbers of these victims desensitize us to their tragedy. Now more than ever, we need to demand scrutiny of police from our legislators. The movement is at a disadvantage in the face of the new administration, but its urgency has never been greater. Don’t forget their faces. Don’t forget their names.

Erin Hill is a sophomore psychology major. She can be reached at erin.mckendry.hill@gmail.com.