Views expressed in opinion columns are the author’s own.

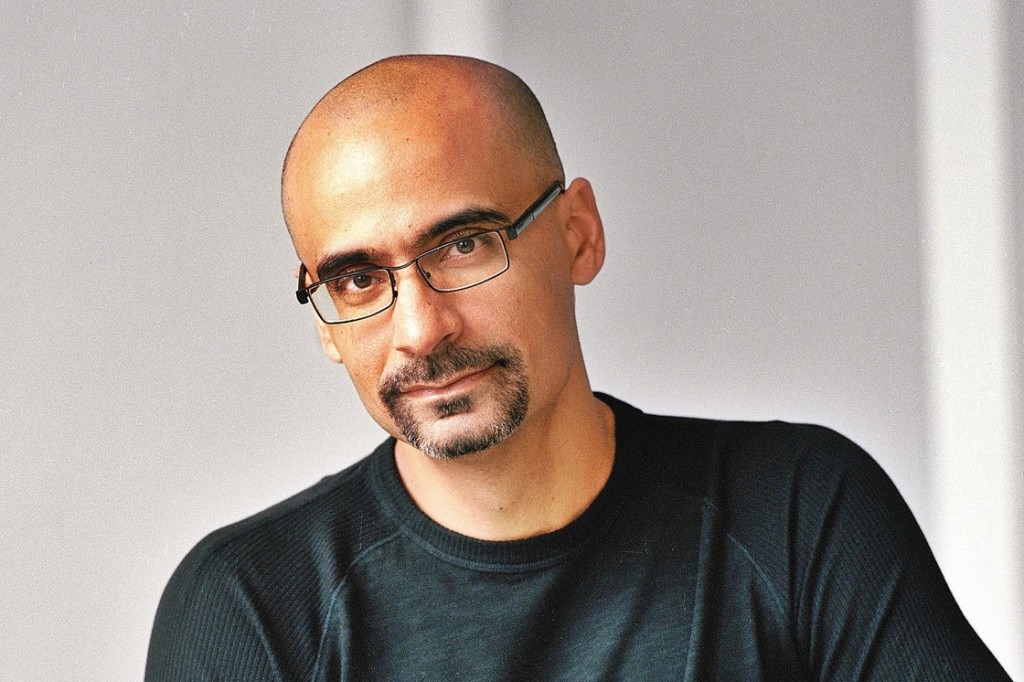

The recent allegations of sexual misconduct and misogynistic behavior against famous Latinx author Junot Díaz come less than a month after he wrote in The New Yorker about how being a victim of sexual assault as a child dramatically altered his life.

As with other men — Harvey Weinstein, Bill Cosby, Kevin Spacey — who have been accused of sexual abuse and violence, the response to Díaz has been swift and pitiless. After being previously held as a hero in Latinx literature, Díaz is being denounced by fellow writers and former fans alike.

[Read more: Stop treating male writers’ abusive behavior as a part of their art]

As a society, we have a habit of socially and culturally banishing those who are uncovered as abusers, and rejecting the consumption of art or entertainment they took part in.

This banishment is important; it demonstrates that we will refuse to pass over the violence these men perpetrate, regardless of how much power they held or adoration they had received. It also brings closure to victims of the violence and makes a strong example out of the men who are caught, hopefully discouraging other men from doing the same.

But this alone won’t eradicate the problems that gave rise to #MeToo. By exiling only specific perpetrators, we ignore that this is a systemic evil, not an individual one. The terrible truth is, the men who have been discovered are not the only ones out there.

The false dichotomy of “bad men” and “men who have not yet been discovered of doing atrocious things” is detrimental to the fight against inequality. It sets a bar separating men who are called out for their heinous actions from those who are still perpetuating patriarchy but have not been discovered to have done anything “bad enough” to be banished. Rape culture and sexism is a part of daily life that is just as harmful — if not more so — than these individual cases of exceptionally bad men.

[Read more: Thanks to the #MeToo movement, Maryland is set to mandate consent education]

If we are to make true progress toward gender equality and the abolition of power-based violence, we cannot ignore the structural and societal influences that make this violence acceptable. We must fight institutional inequalities such as the wage gaps between men and women and between white people and people of other races, as well as the pressure for women to not report sexual assault and the victim-blaming complex that is so rampant in the legal system and society.

Though factors like these may seem unrelated to the things Junot Diaz has done, they cultivate a culture in which men are excused and forgiven for actions that harm others in a cyclical fashion, meaning they promote the same damage that they do to their victims. Diaz’s abuse was verbal and not always physical, but the women he hurt may very well have been influenced by the victim-blaming complex to be fearful of reporting the incidents, because they didn’t want to be called a liar or told that they deserve it.

Men like Weinstein or Cosby or Díaz deserve to be berated and banished as a punishment for the pain they caused their victims to suffer. But instead of just banishment, we need to broaden the discussion to think about how actions, such as catcalling, that seem smaller are just as essential to fight if we truly want to live in a safe and just society.

Michela Dwyer is a freshman philosophy major. She can be reached at mgdwyer3@gmail.com.