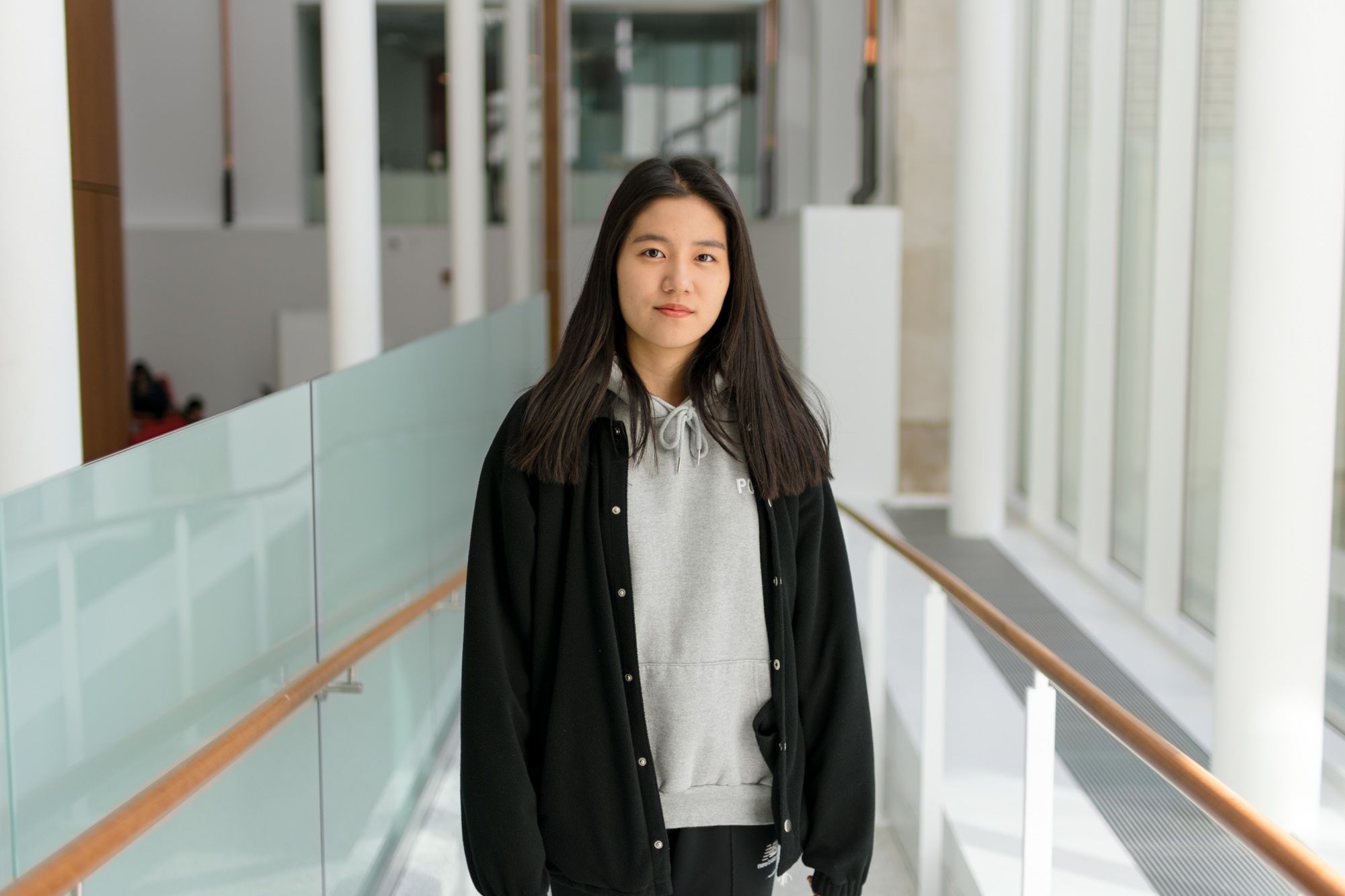

Hyelim Seo was a high school student in Seoul, South Korea when she applied to the University of Maryland to study criminology and criminal justice, hoping to eventually land a job as a police officer, or maybe even a criminal profiler.

But her plans almost ground to a halt when she got her results back from the English language evaluation that non-native speakers must take when applying to this university.

She hadn’t passed, so though she could still come to this university, she’d have to complete an English language proficiency course that would add nearly $5,000 to her tuition bill — a cost Seo worried would burden her parents.

“They didn’t directly say, ‘You’re disappointing us,’ but I could feel it,” Seo said.

Seo, now a freshman, decided to come anyway, particularly because of the university’s highly ranked criminal justice program.

On the campus, Seo struggled to make friends. Initially, she tried to attend events to mingle with other students, but it was exhausting trying to translate her thoughts from Korean to English, she said. Since then, she’s became much more timid.

International students like Seo often grapple with unique challenges that might take a toll on their mental health, said Jinhee Kang, a psychologist at this university’s Counseling Center.

[Read more: University of Maryland to implement a fee for international students]

For Seo, those struggles were exacerbated by the language evaluation. She can’t declare a major until she retakes and passes the test, which has only made her feel more alone.

“I feel like I am very separated from others,” she said. “I feel like I don’t belong to any society right now.”

These challenges include having to communicate solely in a second language and becoming accustomed to an unfamiliar class structure. When Seo started out at this university, she earned low grades in discussion sections since she wasn’t used to participating in classes — in Korea, her professors mainly lectured at students and didn’t ask for their feedback. But lately, she said her grades have been improving.

At the Counseling Center, Kang hosts an international student support group with her colleague David Petersen. Throughout the semester, students in this group meet weekly and share stories about adjusting to life at this university and in America.

“We ask them to start the group together and go through the semester together so they develop trusting relationships and can share challenging experiences and feel safe doing that,” Kang said.

Petersen added that participating in the group also allows students to practice English in a low-pressure setting.

[Read more: UMD stands by “safe space” group for white students to discuss race, despite pushback]

Junior finance major Xiaoran Liu, an exchange student from China, said the most stressful part of adjusting to life at this university has been the language barrier.

“I still feel a little bit uneasy when I speak up in class because everyone looks at me,” Liu said. “I know people can understand what I say, but I still worry about making grammar mistakes.”

Liu isn’t a member of the support group, but she said she’s planning to attend the coffee hour that International Student and Scholar Services hosts weekly to practice her English and make new friends.

The Counseling Center also employs therapists who speak Mandarin, Korean and Spanish to support non-native English speakers and hosts daily walk-in hours specifically for international students.

“They can come in every day of the week at 3 [p.m.] and can be seen by somebody,” Petersen said. “It doesn’t have to be an emergency.”