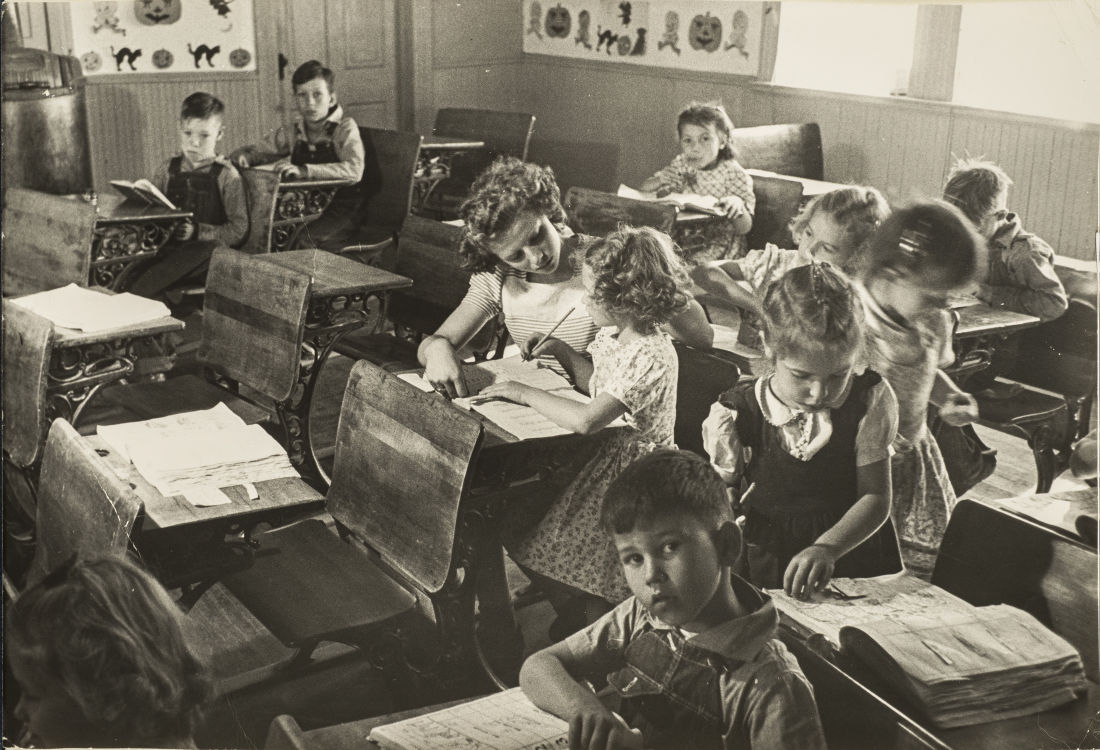

Inside a Wahoo, Nebraska, schoolhouse, Bubley captures children studying at cramped student desks with jack-o’-lantern Halloween posters hanging on the wall.

The photographs of Esther Bubley seem to show what it would be like if Margaret Bourke-White had worked for “The Man.”

Some of Bubley’s earliest works came from her time at the U.S. Office of War Information, but she took some of her most celebrated photos as an employee at Standard Oil and some of her most widely-seen images at the since-shuttered Ladies’ Home Journal and Life, where Bourke-White had published photographs.

Yet the simple fact that she was an active female photojournalist in an age when men dominated the field places her at the forefront of history.

Looking at a new Bubley exhibition at the National Museum of Women in the Arts and speaking with the show’s organizer, Curatorial Assistant Stephanie Midon, one wonders whether Bubley truly wanted to be at that forefront.

At a recent Phillips Collection museum event, Midon asked Bubley’s niece, Jean Bubley, whether her aunt would’ve considered herself a feminist.

“And she answered that she didn’t think that [Bubley] would,” Midon said. “That’s not to say that Bubley’s work doesn’t advance women in photography, because it certainly does, but…if she were here today to answer that question, she would answer simply [that] she was just working.

“From an early age, she wanted to be a photographer, so I don’t think she thought too much about being a woman in the field,” Midon said.

Others thought about it, though.

“At Life, the photo editors were initially hesitant to hire her,” Midon said. “She was a very petite woman and…her demeanor was not as aggressive, frankly, as Bourke-White and other male photographers.

“Many of the photo editors sort-of initially dismissed her, thinking she didn’t have the chutzpah to handle working at Life,” Midon said. “Her work proved them wrong.”

But did it?

Bubley made her first foray into Life not through intrepid reporting of a dangerous situation, but by winning third prize in the magazine’s young photographers’ contest.

She took on her field’s gender barriers not by simply saddling up without trepidation, but by losing the bulky gear common in those days in favor of lighter 35mm film and a point-and-shoot camera that gave her work a spontaneous but underwhelming aesthetic.

She made her living by working freelance for enormous corporations including PepsiCo Inc., Pan American Airways and most notably Standard Oil, the same conglomerate that the great female journalist Ida Tarbell had so decried just decades before.

And while Bubley did not sidestep political or ideological conflict when it happened to grace her lens, she rarely sought it out with the kind of activism her peer Dorothea Lange did.

The question remains if these attributes are negative, positive or neutral. Midon said she thinks that Bubley was just doing her job, and was good at it.

“I think that even though … she was being paid by bigger corporations and publications, at the heart of it she was a photojournalist, she was a documentarian,” Midon said. “Even if the assignment might not specify an idea in particular … I think just in recording everything, she did capture glimpses of bigger social movements.

“In being a true documentarian, she still took note of the larger issues that were happening at the time,” Midon said.

Some photographs in the exhibit capture this, including one that portrays a group of female American Legion color guards, including a black guard, hoisting the flag at Arlington National Cemetery. The image makes a statement about the then-developing race and gender integration of the military.

Bubley’s images of the Wahoo, Nebraska, schoolhouse capture a moment in time. Outside the steep-eaved, one-room school, children eat lunch in the shade, a well pump casts its shadow in the midground and high rows of Nebraska corn peek out from the back. Inside, children study at cramped student desks with jack-o’-lantern Halloween posters hanging on the walls.

Still, upon leaving “Esther Bubley: Up Front,” which opened Sept. 4, one has questions.

It seems Bubley was somebody who, from a young age, wanted to be a photographer. And as a photographer, she was suitably talented, achieving a fantastic career in photojournalism at some of America’s best publications and companies. As a photojournalist, she was fair and prolific.

But it also seems that she was relatively inconsequential. Her work — at least what is on view — is rather tame. She didn’t explicitly pave the way for women in the career and she doesn’t have a solitary magnum opus that defines her, such as Lange’s Migrant Mother or Bourke-White’s Gandhi and His Spinning Wheel.

It seems that she’s only in a museum because she was a woman working at a time when that was wrongly difficult, and because the pieces on view were part of a recent donation. The question posed to visitors as they consider the otherwise praiseworthy show, then, is this:

Is that really a good enough reason?

“Esther Bubley: Up Front” closes Jan. 17, 2016. The NMWA is located near the Metro Center station, and student admission costs $8.