Where do victims find medical resources?

DNA is considered one of the most important tools in finding justice for sexual assault victims, but securing such evidence and putting it to use remains a challenge, advocates said.

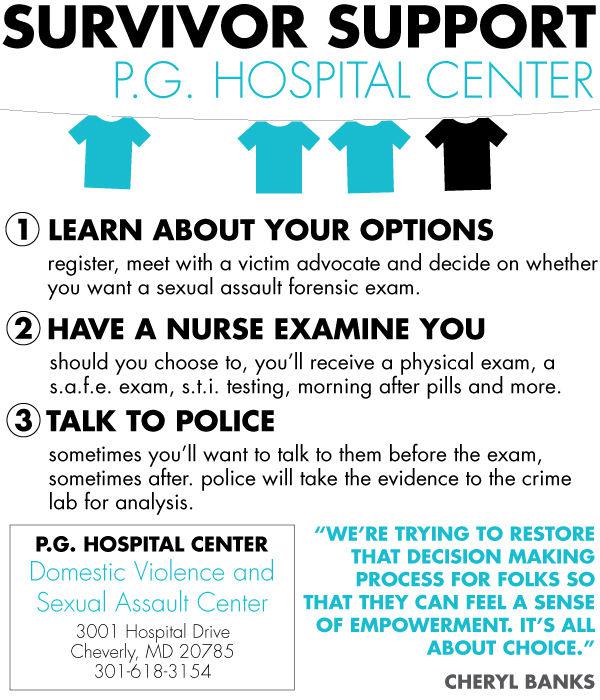

Survivors of sexual assault are able to receive women’s health examinations at the University Health Center, but if they want a sexual assault forensic exam, they must go to Prince George’s Hospital in Cheverly, about 5.5 miles away.

The roughly 15-minute drive from the campus could deter some survivors from reporting the crime, while others may feel more comfortable leaving the campus to seek help, said Cheryl Banks, the community educator and volunteer coordinator for the Domestic Violence and Sexual Assault Center at the hospital.

“For some people it would be more accessible [on the campus] and then they might be more willing to get an exam,” Banks said. “For other people it would be more threatening, because they feel like they will not have the confidentiality and privacy that they do when they leave campus.”

The exam itself can take three to four hours depending on the case, but it has to take place within five days or 120 hours of the assault, Banks said. The Violence Against Women Act of 2005 ensures that these exams are free, even if the survivor chooses not to report the crime. Banks said they do about 200 exams a year.

VAWA grants accounted for almost $2.5 million of spending on sexual assault awareness and victim resources programs in the state of Maryland in fiscal year 2011, according to the Maryland Coalition Against Sexual Assault.

The university does not have forensic nurse examiners — who are specially certified for these exams — on staff nor do they have the equipment for the exam, said Stephanie Rivero, the assistant coordinator of CARE to Stop Violence. However, Rivero said they recently started to research the benefits of having this resource on the campus for survivors.

“There has been some news recently around the country that the idea that having it accessible, having it at the health center would make students more willing to go forward with the [sexual assault forensic exam],” Maj. Marc Limansky said. “I think that has some merit to it. It would probably be worth examining further.”

Sexual assault forensic exams are primarily used to collect evidence for a criminal trial, which is not always the course of action survivors wish to take, Rivero said. At the hospital, Banks said the collected evidence is picked up by police and taken to a crime lab for analysis.

Fear of retaliation, loss of friends, reliving trauma and an uncertain and lengthy legal path can all deter a survivor from wanting to file charges, she said.

These concerns could explain why 60 percent of sexual assaults are not reported to the police, yet 1 out of every 5 undergraduate American women has been the victim of sexual assault, according to the Department of Justice and the White House.

At this university, there were 10 forcible sexual assaults in 2010, five in 2011 and 10 in 2012, according to the most recent Clery Act statistics. Uniform Crime Reporting data also show that no rapes or attempted rapes have been reported since 2011.

Although the numbers are low, university officials said they know the data doesn’t reveal the full story.

In 2010, 2011 and 2012, Prince George’s County was second only to Baltimore City in highest number of reported rapes per county, according to the MCASA.

“With 38,000 people you have to have your head in the sand that there are not sexual assaults, sexual harassment and other forms of relationship violence going on,” university President Wallace Loh said.

Limansky said he recognized that some survivors may be intimidated by the police but he said he wants survivors to know that the police are approachable and there to help.

“We will not let a victim be victimized twice: once by the suspect and second by the system,” Limansky said. “We will do whatever we can to make it, I don’t know what the right word is — it’s not going to be an easy process, it’s not going to be a painless process — but to do whatever we can to help the victim get through the situation.”

If a student reports the crime on the campus, there is a 65-day limit for the entire process and the ultimate punishment for the perpetrator is expulsion, while the punishment in the criminal justice system is jail time and the entire process could take years, Rivero said.

If the survivor chooses to go to the health center, they will be directed to CARE, the only confidential resource on the campus for survivors. They will be told what options they have available, Rivero said.

However, the DVSAC at Prince George’s Hospital makes sure survivors know all of their options: reporting the crime, receiving a forensic exam without a report, or receiving a general exam through the emergency room, Banks said.

Victims don’t have to decide right away if they want to press charges as there is no statute of limitations, Banks said. The shelf life of DNA is indefinite and the county does not destroy the kits, though prosecution is easier when charges are pressed sooner.

They do same-day exams for women who call in, and each one is given a stuffed animal to take home, Banks said, a small token of comfort. The hospital keeps three shelves stocked with toys.

“We’re trying to restore that decision-making process for folks so that they can feel a sense of empowerment. It’s all about choice,” Banks said. “We don’t make anybody do anything they don’t want to do…. The control of their life was taken away when this assault occurred and they need to begin to feel like they can take control of their life back.”