Welcome to DBK + Context, our news analysis and explanatory reporting blog.

Harry Clifton “Curley” Byrd served as University of Maryland president from 1935 to 1954. Under his administration, enrollment more than quadrupled. The campus’s value shot from $5 million to $65 million. He fiercely advocated the terrapin as the school’s official mascot.

Curley Byrd was instrumental in creating the flagship academic and athletic programs the university boasts today.

Recently his name has come up — but not any of the aforementioned reasons. University President Wallace Loh last week created a committee to help decide whether to rename Byrd Stadium after receiving a petition that called its namesake a “symbol of racial hatred.”

READ MORE: Wallace Loh forms a work group to help consider renaming Byrd Stadium

Much of the decision Loh and his committee has to make boils down to one question: Was Curley Byrd a racist?

Short answer: Yes.

Byrd was appointed assistant university president in 1918. At the time, the Supreme Court’s ruling on Plessy v. Ferguson allowed white and black students to receive “separate but equal” educations, and Byrd’s administration barred Thurgood Marshall from attending the all-white University of Maryland School of Law. A few years later, Byrd and then-President Raymond Pearson tried to block Donald Murray, who was black, from entering the school in 1935. Murray sued and won, becoming the first black student to enroll at the law school, after Pearson openly testified he’d been barred because of race.

And of course, it was the Byrd administration that sidelined superstar athlete Wilmeth Sidat-Singh as the Syracuse Orangemen took the field against the Terps in 1937.

But was Byrd really prejudiced at heart — or a helpless victim of federal law and peer pressure?

After the 1938 Supreme Court decision in Gaines v. Canada, in which the court ruled states had to provide white and black students with the same in-state education opportunities, Byrd wrote an administrative letter detailing his alarm.

The Supreme Court went “further than it should, or was necessary,” he opined.

Because there was no other public, in-state institution of higher education at the time, the responsibility to provide this education fell on this university.

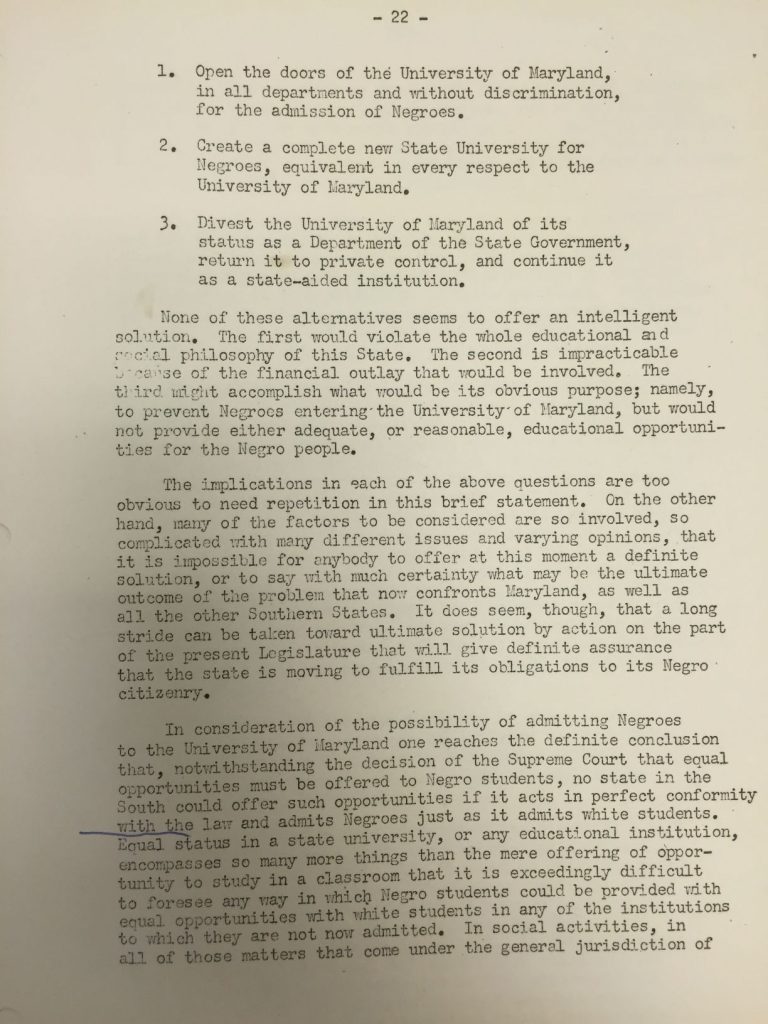

Byrd saw only three options: First, “open the doors” of the university to all students “without discrimination.” Second, create a completely new university for black students only. Third, return the university to private ownership and circumvent the ruling altogether.

Though he considers the third option for a few lines in his letter and points out the obviously impractical financial implication of the second, he dismisses the first option in one sentence:

“The first would violate the whole educational and social philosophy of this state.”

Calling the implications of the options “too obvious” to expand upon, Byrd argued that desegregation would not offer black students the opportunity to “attain a self-supporting place” in their community. He wrote that he feared they’d also be barred from extracurriculars due to — you guessed it — more discrimination.

He settles, finally, on acquiring nearby (and predominantly black) Morgan College and appropriating funds to improve agricultural studies at Princess Anne’s College so it might match College Park’s caliber. Naturally, this allowed the College Park campus to continue turning away black students.

All that, just to avoid the first option.

So, sure, Byrd was instrumental in building a flagship institution, but does his racism mean his name should be removed from Byrd Stadium? That’s for you to decide.

POLL: Should Byrd Stadium get a new name?

LATEST DBK + CONTEXT

[ READ MORE: About that BroBible housing column: Fact-checking Rebecca Martinson ][ READ MORE: The D.C. metro is going paperless – for good ][ READ MORE: Do UMD students get free tuition if they get hit by a Shuttle-UM bus? ][ READ MORE: Wallace Loh faced threats, had police detail after announcing Big Ten move ]

The Byrd Stadium Naming Work Group met for the first time Monday.