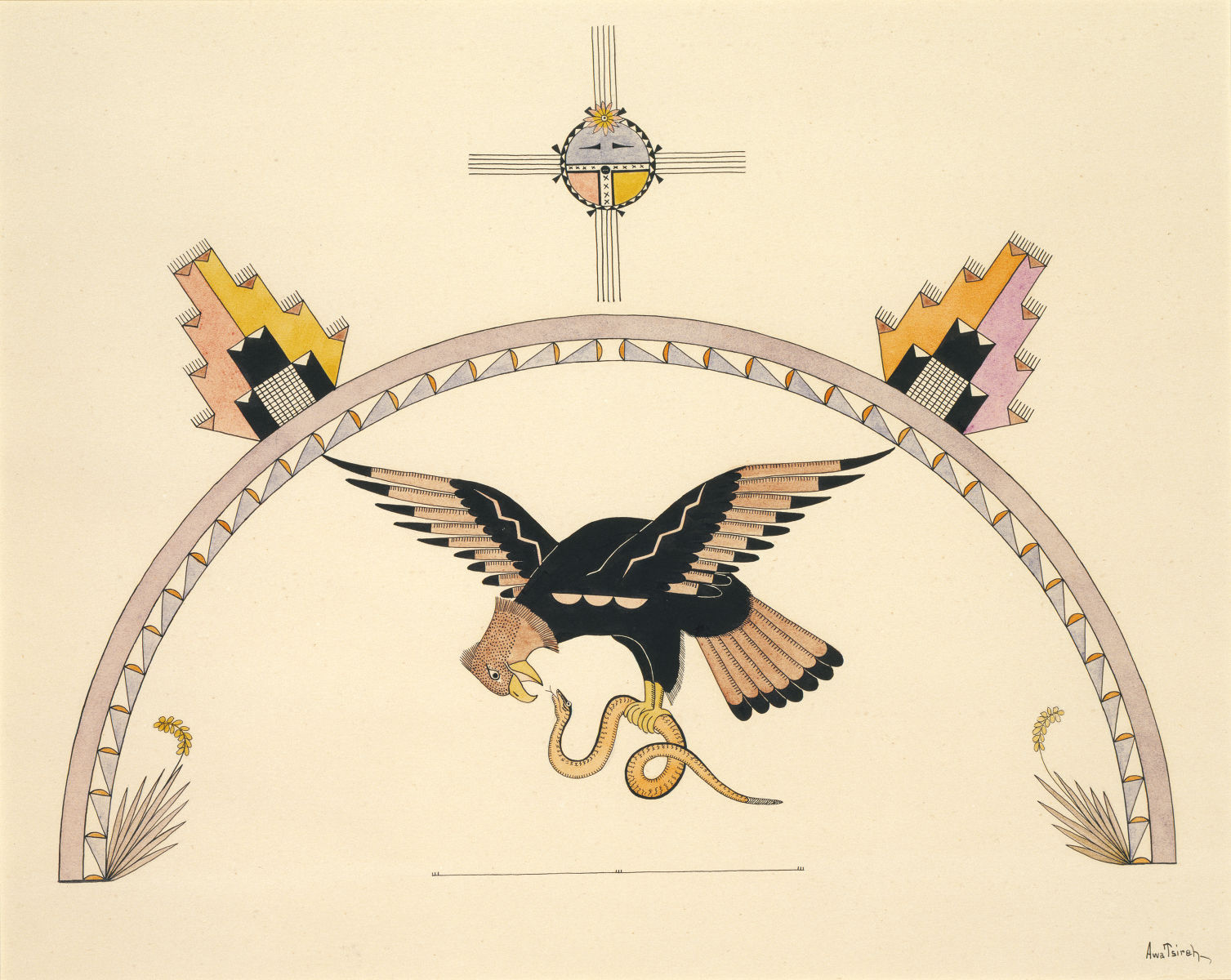

In “Eagle With Snake,” Tsireh uses a common geometric rainbow design to portray an Aztec emblem also seen on the Mexican flag. (Image courtesy of the Smithsonian American Art Museum/Corbin-Henderson Collection/Gift of Alice H. Rossin)

The Smithsonian Institution, by way of its sheer size and purview, has the unique capacity to step heavily on its own toes.

Because it has so many diverse component organizations, what belongs where can prove an open question. Most culturally and historically controversial is the question of what prompts some Native American artists to be exhibited in the National Museum of the American Indian, ostensibly viewed in the context of their own culture, and others to be shown among the annals of all American art in the nearby Smithsonian American Art Museum?

A new exhibition of Pueblo Indian painter Awa Tsireh at SAAM begins to answer that question. Deputy chief curator Joann Moser, who organized the exhibition, explained the perceived possible conflict.

“We have the Museum of [the] American Indian as part of the Smithsonian as well, and I was a little worried at the beginning that they might resent us doing a show,” Moser said. “But in fact they’re very happy that we’re doing this, because they like this artist to be seen in the context of American art and not just marginalized in a more anthropological way.”

Tsireh, who worked in the early- to mid-20th century, presents a key difference from the common conception of Native American art in that his work is visibly connected with other worldwide movements. From ancient Egyptian murals to early Renaissance naturalism, one can see the influence of history in design, medium and color.

Tsireh became familiar with some of these movements through his patrons, American artist William Penhallow Henderson and his wife, poet Alice Corbin Henderson.

“They invited him over to their house, and they didn’t give him any training, [because] they did not want to change his vision too much,” Moser said. “But they did allow him to look in their library, and so he got to see a lot of different types of art from around the world, some of which is reflected in his work.”

“He was exposed to European and American modernism, Japanese woodblock prints, South Asian miniatures [and] Egyptian art through these reproductions in the library of [William] Penhallow Henderson,” Moser said. Tsireh also incorporated Art Deco style, popular during the early 20th century.

In many pieces, profile forms that hark back to Egyptian tomb wall art (with their feet and bodies at directional odds) repeat themselves to evoke the rhythm of Native American ceremonies, Moser said. In later works, bright colors and geometric forms echo the Art Deco that was taking hold in America’s metropolises.

While the style is intrinsically Native American, Tsireh is traveling far outside his culture to portray his subjects — much as Mary Cassatt brought an American sensibility to her impressionist work in France or as El Greco used his Greek iconography to influence his Spanish painting.

Moser was quick, however, to minimize any causation between the white patrons and the works’ worldliness (using the word “Anglo,” a root of “English,” to describe non-Native American people).

“One of the things that is sort of a touchy thing … is [that] some people have given maybe too much emphasis toward the Anglo influence on getting these works done,” Moser said.

“Indeed, the Anglo patrons were important,” Moser continued. “But it was the Indians who chose the imagery and who chose the designs. I mean, they really had control of what they were showing.”

Is there any reason, though, why this disputes or minimizes the visual references to other worldwide styles Tsireh might have learned in the Hendersons’ library? In this critic’s opinion, no.

If anything, it is further evidence of how worldly an artist Tsireh truly was, even with his limited historical resources. How Tsireh interacted even with other Indian tribes can be seen as supporting evidence to this claim.

In artwork, he not only portrays the rituals of his own San Ildefonso Pueblo, but also those of Navajo, Hopi and indigenous Mexican tribes he knew. In one, Tsireh shows an eagle devouring a snake, the Aztec emblem that adorns the Mexican flag. Above a geometric rainbow shape, the crosshair sun symbol of New Mexico’s flag is also present.

In one later work, Tsireh blends two influences at once. He portrays a Hopi girl with a Kachina (a doll representing a spiritual being) in stunningly naturalistic 3-D. For the first time in the show, Tsireh abandons absolute profile. People have form and mass: Their cheeks puff out and their robes fold and pool with the same weightiness that the first naturalist painters of the early Renaissance once stumbled upon. One wonders whether Tsireh ever encountered a similarly painted angel or cherub holding some Christian spiritual talisman in the library. One wonders.

This angle on the broader context of art history adds a historic value to a historically undervalued segment of art. The patrons, Moser said, “made it possible to value these cultures in a way that they hadn’t been valued before.”