“I was hooked from the first line: ‘Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.’” — Jonathan Raeder

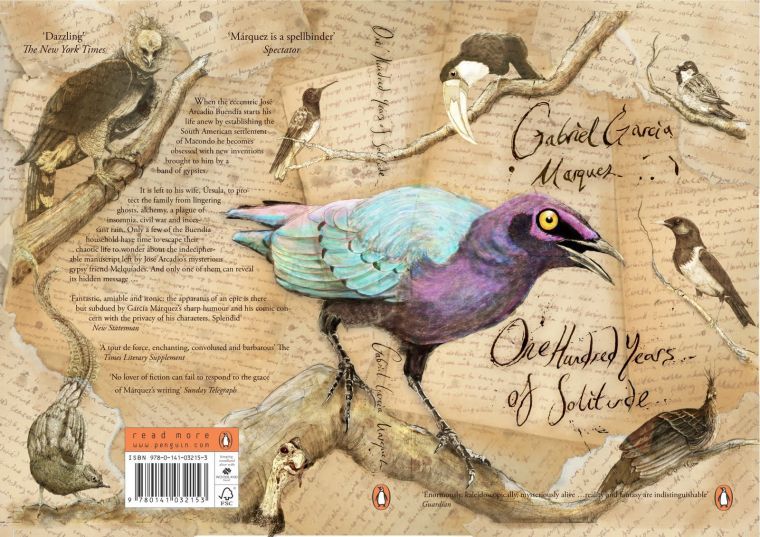

Last week, the world lost one of its greatest writers: Colombian master of magical realism Gabriel García Márquez, affectionately known as Gabo. Gabo left a legacy of amazing work charged with a sense of wonder, love and political criticism. He’s arguably most famous for one book, the masterpiece One Hundred Years of Solitude.

As an English major, I’ve spent a lot of time immersed in the world of contemporary “literature,” and while some works definitely have value, there’s a trend of portraying the world as it is, of strictly adhering to showing truths in explicitly normal situations. That’s valuable, and I don’t mean to belittle it, but I read for more than just recognition — I’m looking for wonder. I want to see something strange, read about something I’ve never read about before and experience wonderful and fantastic events I never could have anticipated.

A few years ago, I was looking for such a book, something that retained a sense of the mythic, of the imaginative, while also being well-written, moving and generally just a fantastic read. I found it in One Hundred Years of Solitude.

I was hooked from the first line: “Many years later, as he faced the firing squad, Colonel Aureliano Buendía was to remember that distant afternoon when his father took him to discover ice.” Why was this colonel facing the firing squad? What was so special about that afternoon? Why does anyone need to discover ice? I had to know the answers, and I hardly did anything over the next few days except sit outside in the summer air and immerse myself in Gabo’s world.

The novel chronicles the lives of seven generations of the Buendía family in the fictional village of Macondo over — of course — 100 years. It’s a magical place, visited over the centuries by a repeating pattern of history: war, destruction, ghosts, love, sex and family issues. Many characters are given the names of their ancestors, so it’s sometimes confusing to keep track of everyone. Regardless, they’re all well-realized characters, doomed to repeat the mistakes of their forefathers and desperately trying to live up or down to their namesakes. The village undergoes massive changes over the century, yet the cycle of life, the changing political leadership that never amounts to anything new and the Buendía family persevere.

In true magical realist form, One Hundred Years of Solitude portrays fantastical events the same way as normal ones, narrated in a voice that echoes the great storytellers of the time before writing. Gabo once remarked he was inspired by the way his grandmother told legends and stories — a man rising from the dead would be described in the same way as someone eating dinner. The ordinary and the bizarre, right next to each other, all inherent parts of life.

Gabo was held in such high regard in part because of his ability to merge the ordinary aspects of life, death, love and family with the strange, the surreal and the mystical. To name just a few of the strange events of this novel: The dead return to remind the living of their faults; a trickle of blood travels across the town, looping over stairs and down roads until it reaches the wife of the man it came from; a silent girl carries her parents’ bones in a bag and eats whitewash from her house; a man has 17 sons, all bearing his name and marked by permanent Ash Wednesday crosses on their foreheads; and a woman ascends into heaven for being too beautiful for the world. There are many more amazing events in these 100 years, but I’ll leave them for you to discover.

Every time I read it, I can’t help but feel a sense of sadness as I discover each generation only to watch it fade away. Most of the characters lead difficult lives with unhappy ends. It’s not a happy story, but its darkness is tinged with an inevitable love, a sense of compassion for humanity, regardless of our faults and endless fights. This story is poignant, despite its otherworldliness, and it’s the emotion Gabo conveys, as well as his portrayal of the political problems of Macondo (and therefore Colombia) that has maintained the novel’s popularity since its publication in 1967. It is, quite rightly, hailed as a masterpiece not only of magical realism, but also of literature in general.

One Hundred Years of Solitude is one of my favorite novels of all time. It’s beautifully written, filled with wondrous imagery and a fascinating story about one family and one town told over a century. It’s hard to read the novel and not reflect on what patterns and cycles we’re still repeating from, say, 1914 — 100 years ago. Technology has changed, yet are we really any different as human beings? We still fight; we still kill; the new boss is the same as the old boss; and our families are just as dysfunctional. What about 200 years ago, 300 years ago? In many ways time is a circle, and One Hundred Years of Solitude is another reminder of the love and the hate humanity will continue to live with until one day the winds of change sweep us away, too. Gabo, the world, and this reader, will miss you.