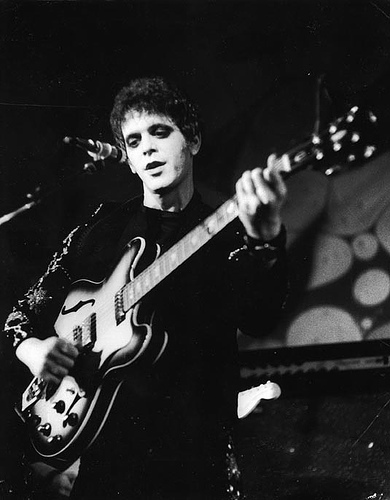

Lou Reed, a legend both for his stint with The Velvet Underground and for his prolific solo career, survived heroin addiction only to be felled by a bad liver. He may be gone but his legacy lives on.

Brian Eno supposedly once quipped that every single person who bought one of 30,000 copies of The Velvet Underground & Nico in its first five years started a band after listening. Released in 1967, the album was The Velvet Underground’s stunning debut.

With the artistic recommendation of Andy Warhol, the bizarre musical experimentation of John Cale and, most importantly, the devastatingly candid songwriting of frontman Lou Reed — who died Sunday — the record was a commercial flop that wound up an immutable classic. Even now, its influence continues to reverberate throughout the music industry.

This speaks to the genius of the late, great Reed. Though The Velvet Underground never amounted to much in the way of sales, his poeticism and delivery earned it a crucial spot in the hearts of other influential artists who are too numerous to name.

As a singer, Reed’s vocals were bewitching, like a stark-black wall, with depth conveyed through simplicity. He was Jim Morrison without the pompous jazz, Bob Dylan without the extended metaphor. He never cared about critics and he probably didn’t care much for listeners either. His only concern was the art.

Because of this, Reed never had a problem innovating. His main technical contribution to music was the “ostrich guitar,” a term used to describe a guitar with all of its strings tuned to D, which inadvertently led to a tendency toward elementary song construction and would later usher in the punk movement. More than anything, though, it was his attitude that left the deepest impression.

Reed was among the first rock musicians to write about dark, complex issues. Possibly a bisexual man himself, he plunged into sexuality, as well as addiction and alienation, in his often controversial and never predictable lyrics. His refusal to clean up songs for the timidity of the music industry in the late ’60s and ’70s prevented him from reaching total stardom yet preserved his legend.

Playful denouncements of convention like those in his well-known “Walk On the Wild Side” were among his best moments as a songwriter. “But she never lost her head/ even when she was giving head,” he sings on that track without so much as a snicker. Another example of his distinctive approach to songwriting comes in “I’m Waiting for the Man,”a roughly 4-minute narration about heading uptown to score some heroin.

The most obvious indication of Lou Reed’s importance came in the reaction after his death from known public figures not immediately associated with him. Samuel L. Jackson tweeted, “R.I.P. Lou Reed. Just met at the GQ Awards. The music of my generation. Still Relevant!” Meanwhile, Judd Apatow posted, “I met Lou Reed and told him he gave me tinnitus at a concert in 1989 that never went away and it was worth it. Dirty Blvd. Love to Lou.”

Reed’s death had much of the Internet buzzing Sunday, with even complete strangers confessing their grief over his passing. This was a man whose music found an unexplainable way to connect people to one another and to himself. In the midst of all the iconic musicians to surface in the 1960s, Reed was a once-in-a-generation talent who will surely be missed — the type who lives on indefinitely through those who were touched by his music.

Has he died in a physical sense? Yes. Has he died in a figurative one? Not at all. His musical contributions in life will carry on for decades beyond his death, and that’s something to celebrate in itself.

So, thanks for the 71 years of perfect days, Lou. We’re glad we could spend them with you.