Kevin Anderson came to the university more than a year ago to helm the ACC’s third-largest athletics program. But the one he’s in charge of this year will be almost unrecognizable from the one he stepped into.

Just months after Anderson was named the new athletic director, he faced a crushing deficit. The department had been experiencing budget shortfalls since 2006, but last year, officials realized the program was simply unsustainable.

University President Wallace Loh tasked a working group in July to examine the athletics department’s financial situation, which included an $83 million debt. And, for the first time, the department couldn’t balance its budget in fiscal year 2011. The department expected the deficit to amount to about $4.7 million, and reserves had been completely depleted.

If something within the department didn’t change - and soon - the deficits would keep mounting; they would have risen upwards of $17 million by 2017. Officials couldn’t maintain the cost of the department’s 27 varsity sports program – the third-largest program of the 12 ACC schools.

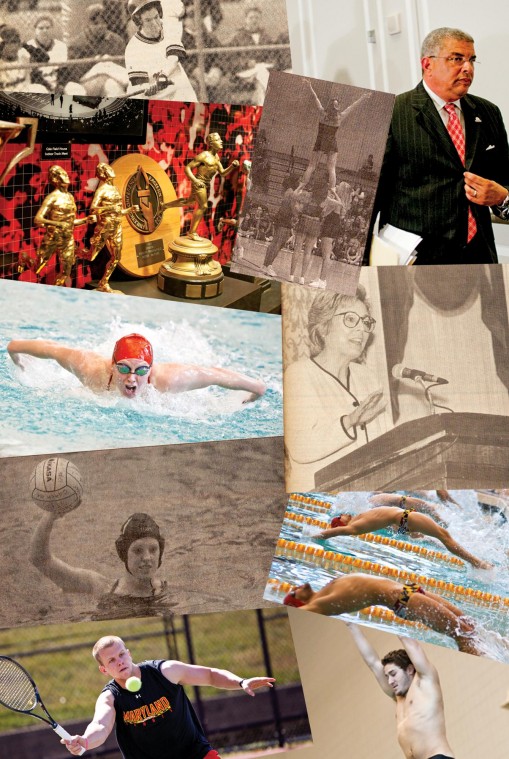

In November, Loh faced what he called the most difficult decision he’s ever made. He cut eight teams – men’s and women’s swimming and diving, men’s cross country, men’s indoor track, men’s outdoor track, men’s tennis, acrobatics and tumbling and water polo – to balance the budget.

Anderson issued a recommendation to give the teams a chance to survive. They have until June 30 to raise the funds necessary to fund their programs for the next eight years, and two senior athletic officials have aided the efforts. But with just more than a month until the deadline, only one team - men’s outdoor track - seems to have a viable chance at returning next year.

The athletics department Anderson will oversee won’t be the massive program former Director Debbie Yow built up. It’ll likely be a 20-sport program with better funded teams, ushering in a new era for university athletics.

“For right now, yes, this is the answer,” Anderson said. “I think it’s a national problem, and in some way, shape or form, we’re going to have to put our arms around the mounting cost of competing, and there’s going to have to be some solutions somewhere.”

A PIONEER

Much of the program’s growth stemmed from Title IX requirements, which stipulate the university must provide equal athletic opportunities to women through scholarships and funding, relative to their enrollment in the student population.

In 1992, the NCAA stated the university was violating the 20-year law.

When Yow took over in August 1994, she encountered a budget debacle similar to the one Anderson inherited: The department had not generated enough revenue to pay its bills for 10 consecutive years and was incurring millions of dollars in annual deficits. She was tasked with balancing the budget while also finding a way to ensure men’s and women’s teams remained equally funded.

The men’s teams were performing poorly in ACC competition; officials wanted to be able to provide more scholarships to the teams to help make them more competitive. The answer, they decided, was to add more women’s teams.

A softball team, a water polo team and acrobatics and tumbling all formed under Yow’s tenure. Soon, she was overseeing 12 men’s teams and 15 women’s teams and captured 20 national championships – 17 of which were from women’s teams.

While some thought the addition of the new teams had helped legitimize more women’s sports, others thought the university was finding the cheapest way to remain in compliance with Title IX.

“It seems like they’re looking for the easiest way out, that their intent is to conform to the letter of the law, but not necessarily the spirit,” Donna Lopiano, the CEO of the Women’s Sports Foundation, told The Washington Post in 2003. “If they had club teams that wanted varsity status, why go and manufacture one out of cheerleaders?”

But Lura Fleece, the acrobatics and tumbling coach when the team was founded in 2003, said the team’s varsity status was long overdue.

“We basically had been granted what we had been asking for for years and years and years,” Fleece said. “That was to be considered athletes.”

The university was seen as a pioneer in spearheading more competitive women’s sports. Although water polo and competitive cheer started with small amounts of funding, they eventually gained more financial support.

“In the early days, my budget was not what I needed it to be,” water polo coach Carl Salyer said, “but they were very understanding, and every year my budget grew and gave me more resources.”

Within a few years of Yow’s arrival, the department was experiencing unprecedented success. Ticket sales had skyrocketed from 2001 to 2002, and the men’s basketball team captured its first-ever NCAA championship in 2002. Yow’s athletics program was a new, potentially innovative model to remaining Title IX compliant.

THE CRASH

The financial upswing didn’t last long.

By 2006, the department began experiencing budget shortfalls, which continued for the next five years. The university had enough in reserves to balance its deficit until 2010, which created the illusion of a balanced budget.

In 2009, the university debuted Byrd Stadium’s Tyser Towers, a $50.8 million project boasting 63 luxury suites and flat-screen TVs, hoping to lure alumni into buying season tickets. But as the football team’s performance on the field deteriorated – it generated nearly $2 million less revenue in 2010 compared to 2006, according to the commission’s report – officials had trouble selling the seats.

“It’s very hard to raise money in the aftermath of the Great Recession,” Loh said. “That’s why we didn’t sell and still haven’t sold all those wonderful suites in Byrd Stadium.”

Slumping ticket sales, combined with the multimillion dollar investment that didn’t pay itself out, proved to be catastrophic.

A NEW MODEL

The last thing Loh wanted to do was alter the future of hundreds of student-athletes. But he simply didn’t have another option.

“You have 75 members of a team, and they’re crying and you just feel awful. That’s when the weight and the burdens of office really weigh onto you,” he said. “It’s not just, ‘We’ll balance the budget.’ It’s about people’s lives, and there’s no way you can communicate that. There’s no way you can prepare for that until you’re in the job.”

Loh and Anderson never want to have to face this problem again. They didn’t want to cut the teams; they hoped alumni support combined with the help of two staff members would help keep them at this university.

For the past six months, several of the teams have struggled to come close to the millions of dollars needed to stay.

Loh and Anderson hoped it wouldn’t come to this. But they have had to turn their attention to the remaining teams and the new model they hope will prevent future crises.

“What we’re looking at now with other sports is creating endowments, so that if rough times hit again, we have a contingency plan and a financial model that we would be able to tap into to fight off situations that we’re facing now,” Anderson said.

The department also hopes to better fund each athlete. This university ranks last of the ACC’s 12 institutions in how much it spends per student-athlete. It spends about $67,390 per student-athlete, compared to the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill - a 28-sport program- which spends about $78,430 per student.

“We could have looked at reducing all the budgets … but there had already been drastic budget cuts to the 27 programs,” Anderson said. “To reduce their budgets any more would jeopardize the competitiveness of the teams.”

Although nothing will be official before July 1, several coaches and student-athletes have come to terms with the fact that this university’s athletics will have an entirely different face in the coming weeks and years.

“The motto … has been 27-1 – 27 teams, one goal,” track and field coach Andrew Valmon said. “Everything was ‘Fear the Turtle.’ All those signs have to be changed.”

For a university that had once prided itself on providing so many new opportunities, the change won’t be easy.

“Nobody ever wants to cut sports, period,” Salyer said. “It’s a black eye on the department, and it’s a black eye on the university. But black eyes can heal.”

abutaleb@umdbk.com, lurye@umdbk.com