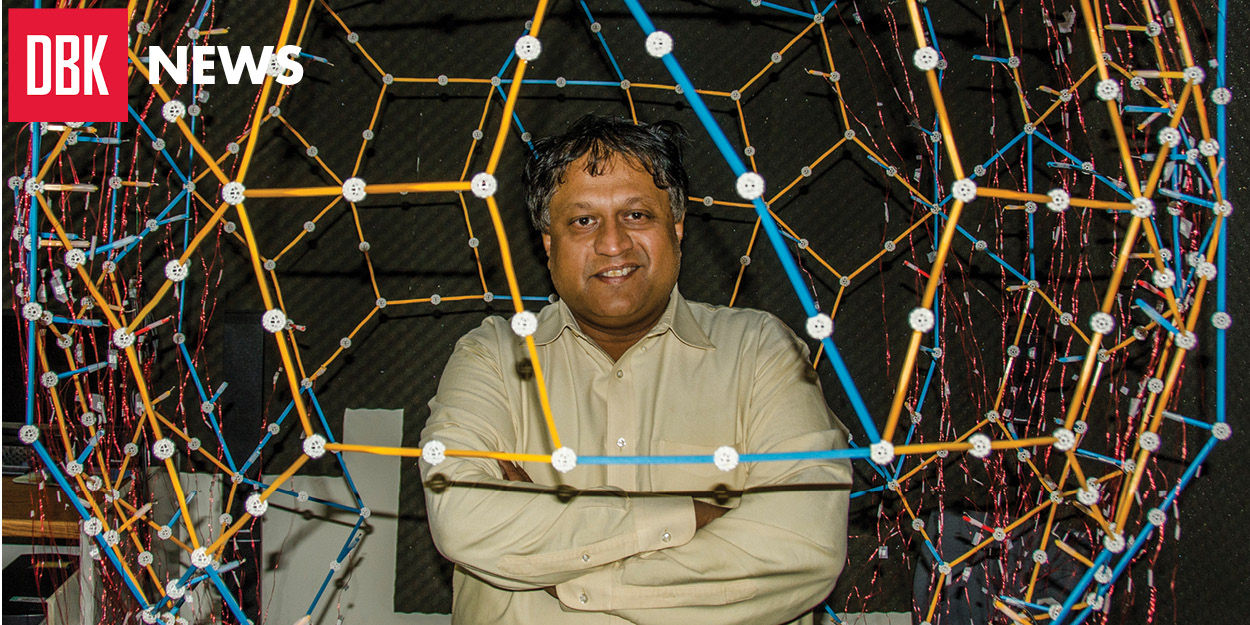

Computer science professor Ramani Duraiswami has sold licensing rights to Oculus VR.

It looks like a little gray box. But when you move it through the air, it sounds more as though you’re moving a whole orchestra around the room in the palm of your hand.

Technology developed at the university makes it seem as though the music is coming from this sensor, but really it is just because the headphones can make sound seem as though it is coming from any direction and distance. This technology has captured the interest of Oculus VR.

Weeks after Oculus VR co-founder Michael Antonov, CEO Brendan Iribe and Iribe’s mother donated a combined $38 million to the university, the company has announced they will use technology developed at the university in its future virtual reality headsets.

The tech company has bought the licensing rights to use the audio technology from VisiSonics, a startup company founded by computer science professor Ramani Duraiswami and other university researchers. Their technology works to create a realistic presentation of sound in a 3-D space, Duraiswami said.

“Audio is an essential ingredient for immersive virtual reality,” Iribe wrote in an email statement. “The technology that the VisiSonics team has developed is a great start towards developing a fully-featured VR audio solution, and we’re incredibly excited to be licensing their work to drive VR forward.”

Typical headphones use stereo sound and little more than panning or fading to crudely recreate sound that is supposed to be farther away, Duraiswami said. But with the technology from his lab, a user can hear something as though they are really experiencing it.

“When you go to a movie theater, there’s a whole array of speakers around you, so if a sounds comes from a certain direction, the speaker over there goes off,” said Amitabh Varshney, director of this university’s Institute for Advanced Computer Studies and a computer science professor. “Dr. Duraiswami can recreate that whole experience in one pair of headphones.”

This realistic audio, which Oculus VR has incorporated into prototypes for the new Oculus Rift headset, has obvious applications for video games, said Dmitry Zotkin, a computer science professor and VisiSonics researcher.

“In a virtual reality game, you can know where a sound is coming from,” Zotkin said. “You can know if it is another player or if it is a tank, or a helicopter, or monsters or footsteps, and you know exactly where it is from the sound. This not only accounts for the direction but the distance of the object.”

In order to make sound as accurate to life as possible, Duraiswami and his team do more than just account for direction. They also account for the unique shape of each person’s ears.

“When the sound is received by your body, it changes the sound slightly,” Duraiswami said. They can measure the way each person will hear a sound differently by finding what they call their head-related transfer function, or HRTF, and then adjusting the sound for specific ear shapes. “We’ve figured out how to measure HRTFs very quickly, in seconds. We can use hearing tests or even photographs of ears to determine the HRTF of any individual. All this together gives us a lot of information that we can use to make the virtual world more realistic.”

Duraiswami’s lab can also use its VisiSonics RealSpace Panoramic Audio Camera, which is a sphere covered on all sides with cameras and microphones, to track sound in 3-D space. Duraiswami demonstrated this by showing a video of a visualization of a single clap moving and reverberating through the Clarice Smith Performing Arts Center. Then he showed a video of a noisy bar, where he was able to isolate a single conversation because of the directional headphones.

VisiSonics, which was founded with the help of the Office of Technology Commercialization, is a success story for start-ups at the university, which is a hotbed for entrepreneurship, said Gayatri Varma, the office’s executive director. The office aims to take the research of university professors and make it marketable for public consumption.

“You need to have these start-ups to bring these ideas to the market place,” Varma said. She noted how the licensing of VisiSonics’ technology represented a special success because of Oculus VR CEO Brendan Iribe’s special connection with the university as a former student. “This is something we like to see. It’s great because not only is their technology being used, but it’s a UMD alum who came back and bought it.”

As Oculus VR uses its technology, VisiSonics will use the money from the licensing deal to further develop its technology for virtual reality, Duraiswami said.

“This is another example,” Varshney said, “of how Oculus is helping us become the No. 1 university in virtual reality in the world.”