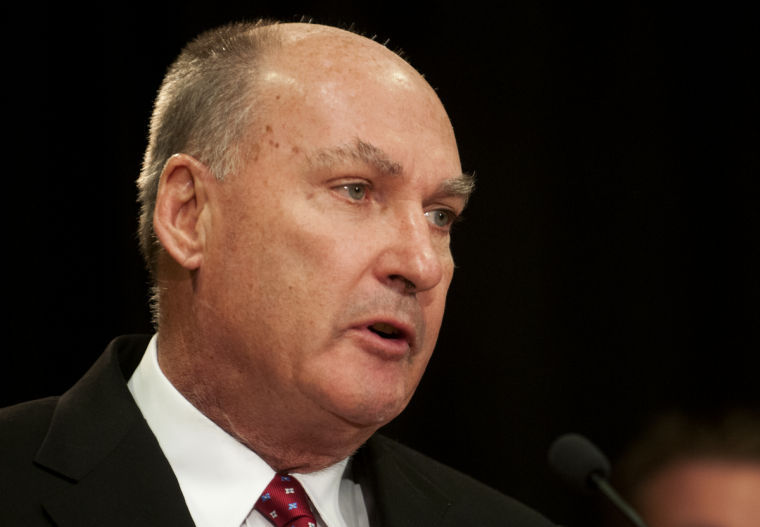

Big Ten commissioner Jim Delany.

Conference realignments are nothing new to Jim Delany. He’s seen plenty play out in the 24 years since becoming Big Ten commissioner, with even his own conference dramatically reshaping in that time.

When he oversaw Nebraska’s move from the Big 12 to the Big Ten in 2010, Delany thought his conference was set. But he was seeing something new take hold across the country. Conferences weren’t simply adding or losing members, he realized. They were expanding geographically. It wasn’t enough to have members in only one region of the country because a wider audience meant better TV contracts, which meant more financial security.

So a couple of years ago, Delany thought of university President Wallace Loh. He thought of this university’s proximity to major media markets in Washington and Baltimore. He thought about the similarities between the university and the conference’s dozen members, about how the university was also a flagship institution committed to research.

For the most part, their partnership, solidified in the university’s agreement to join the Big Ten before the 2014 athletic season, has been mutually beneficial, Delany and Loh have both said. But if the move is to be truly successful in the long term, Delany said, the university will have to strengthen its financial backing among graduates and alumni and play its way to more of a presence in major media markets — and that can only come from top-notch revenue sports teams that rake in wins and championships.

“I think Maryland is a great university, has had good success, but not great success, in recent years,” Delany told The Diamondback. “It’ll be important to us for Maryland to be successful and in any partnership, both partners should improve and get better as a result of that partnership.”

Loh announced the school’s decision to leave the ACC on Nov. 19, and university officials have since spoken of the benefits of the conference’s revenue-sharing model and the increased academic opportunities offered by membership in the Committee on Institutional Cooperation, an academic consortium of member schools and the University of Chicago.

Unlike most of the Big Ten’s members, however, this university isn’t a football-first school, much less a powerhouse. Byrd Stadium doesn’t often sell out; indeed, slumping ticket sales contributed to the athletic department’s financial struggles and, ultimately, Loh’s openness to a more lucrative conference affiliation.

Perhaps most importantly, the university’s alumni and fan base, in terms of booster support, fall well short of the likes of the University of Michigan, the University of Wisconsin and Ohio State University. And that’s why there will have to be improvements if the move is going to work in the long term, Delany said.

But he’s confident it will. So is Loh.

“We want to be top-20 in athletics, which is not going to happen overnight, but we’re going to go down that path,” Loh said. “If you’re going to go down that path, we need to have the resources to do it. And we’re never going to get the resources in the ACC, not because there’s anything wrong with the ACC, but just because it’s a totally different ball game.”

That goal seemed far-reaching and increasingly unattainable on the athletic department’s previous path. It had been hemorrhaging money for several years, causing the deficit to balloon to a projected $4.7 million in fiscal year 2011. That prompted Loh and Athletic Director Kevin Anderson to cut seven varsity teams, some of which they plan to later bring back with revenue from the conference shift. Before the cuts, the university ranked last among the ACC’s 12 schools in student-athlete support, with $67,390 spent per student-athlete.

“This is really going to benefit how we take care of our student-athletes,” Anderson said of the move. “This is going to give us an opportunity to invest more.”

But the onus isn’t just on the university to adjust to the rigors of joining the Big Ten. The conference is equally obliged, Delany said, to strengthen its presence on the East Coast, so this university’s fans are as passionate about competition at Northwestern as they are at North Carolina.

“If you expand your footprint, you have an obligation to build relationships, build friends, make competitions friendly — and there’s a lot of competition in this footprint,” he said. “There will be more competition, more games, and we’ll try to do it in a way … that reinforces fans and alumni and students in all locations.”

Many have speculated that the Big Ten is hardly done changing, that another ACC school could soon follow the university’s lead. But Delany declined to comment on further changes, maintaining he is “100 percent focused” on the addition of this university and Rutgers, which announced its departure from the Big East on Nov. 20.

Once this university and Rutgers join, the conference will have a trio of schools on the eastern corridor — Penn State has been a member of the conference for 20 years — and those media markets are different beasts. While Midwestern markets are dense and populous, the conference’s East Coast schools reach into Washington, New York City and Philadelphia, all major national cities. There seems untapped potential for growth.

For the time being, university and Big Ten officials alike say they will do everything in their power to plan and prepare for the impending changes. At the end of the day, though, Delany can’t be certain how it will all play out — the product on the field will decide that.

“I’m very hopeful that Maryland has success, that its programs prosper, because I think that will lead to more fan interest, more fan affinity, more support for the university that will eventually make the expansion appear to be successful,” he said. “If you’re a successful member of the Big Ten, you’re going to be nationally relevant.”