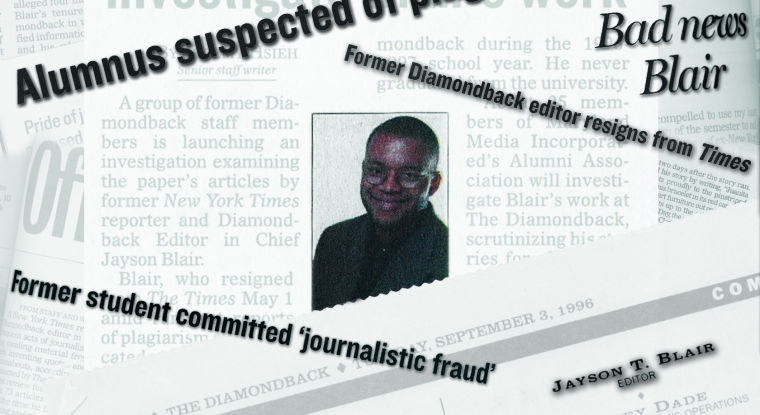

Bad news Blair

Editor’s note: This is part one of a three-part feature on Jayson Blair’s rise and fall. Check out Wednesday’s story of Blair’s resignation from the Times and Friday’s story for the lessons learned at this university a decade later.

Jayson Blair had grown intolerable.

“Just go already,” the 1997 staff members of The Diamondback quietly whispered among themselves.

Blair, the daily independent student newspaper’s 1996-97 editor in chief, walked out the newsroom doors for the final time in April 1997. After a reign full of missed deadlines, questionable ethics and little leadership, the staff was ready to move on. They threw a party to celebrate a fresh start under Danielle Newman’s leadership.

The lyrics, “You can’t hide your lyin’ eyes,” rang through the newsroom. It was a line from an Eagles song, “Lyin’ Eyes,” the anthem for the 1996-97 Diamondback staff, which had grown infuriated with its editor in chief, who members said constantly lied to them.

Blair, who declined several requests for comment, ended his tenure early without citing a reason, staff members said. About a year later, he landed a job at The New York Times, where he went on to destroy his journalistic career and may have cost two high-level Times editors their jobs in 2003 after an internal investigation found he plagiarized and fabricated dozens of stories. The cataclysmic incident was unfathomable at a place like the Times, a place reserved for journalism’s most elite players.

Blair resigned from the Times nearly 10 years ago on May 1, 2003. It surprised many journalism college faculty members, who saw Blair as an eager — albeit immature — and promising young black reporter who could improve diversity in the newsroom.

But it was hardly surprising for the students who had worked alongside him at The Diamondback in his two years there. He lied both as a reporter and editor in chief of the paper, staff members said, yet remained a favorite among journalism college faculty. He continued to receive strong recommendations to help secure high-profile internships and served as a reminder of life’s unfairness, former Diamondback staff members remembered.

If he continued down the treacherous path he began at the student newspaper, his contemporaries knew his disgraceful fall from journalism was inevitable.

“It was cynical, but it was like, ‘Oh my God, he finally got his comeuppance,’” said Newman, who took over as editor in chief the night Blair left. “He got busted. It took a long time for him to get busted. He should’ve gotten busted earlier.”

WARNING SIGNS

That Blair kid was everywhere, staff members recalled. He had just started writing for The Diamondback in January 1995, but he immediately took to gossiping and socializing. His distinct cackle — a cross between a hyena and Woody Woodpecker, said Tom Madigan, who worked with Blair as a sports editor and later ombudsman — became well known throughout the newsroom and journalism college.

“It was impossible not to know Jayson — he was everywhere,” said Carl Stepp, a journalism college professor. “He was the best schmoozer as a student I’ve ever seen.”

Sure, he was often annoying, staff members said, but he was harmless.

“It was easy to forgive that sort of thing because there was something sort of cute about it,” Madigan said. “He was nonthreatening. He was just an overeager kid, and he made a few mistakes, but so does everybody.”

But Blair’s personality only took him so far before his work began to speak for itself. He was sloppy, staffers said, and he had a poor work ethic. He turned in his articles late and continually made careless errors.

So editors worked with him and gave him tips to improve. He would vigorously nod in response.

“Yeah, yeah, yeah, I got it,” he’d say over and over, Madigan recounted.

“He really, really wanted you to know he was listening to you,” Madigan added. “None of these amounted to a red flag, exactly. It was just a kid trying a little bit too hard to fit in.”

Blair knew how to smooth talk, journalism faculty and Diamondback colleagues said, which helped his reporting. Despite his minor errors, he still landed on the front page several days a week.

And strangely, Blair requested his middle initial be placed on his byline, which some staff members said they found presumptuous. “Jayson T. Blair,” it read.

But the staff could deal with those little annoyances. The real problems surfaced when his lack of reporting — and eventually, fabrication — became evident.

When Blair went out with another reporter to gather quotes for a story one night, he came back with a handful of quotes. But the reporter didn’t see Blair talk to anyone, Newman said.

Editors called the registrar’s office to check the names of students Blair had provided. None of them were listed students at this university.

He wasn’t having the same problems in class, however. Chris Harvey, now the journalism college’s internship and career development director, who taught Blair in an intensive reporting class, remembered checking the source lists she required from all of her students. She called the sources herself to make sure students had actually talked to everyone listed. And Blair’s list checked out, she said.

Diamondback editors didn’t do an exhaustive investigation of all his stories, Newman said. But Blair was fired after he failed to turn in three stories during one semester — then a minimum standard required from any staff writer. Blair left and worked for Capital News Service, the journalism college-owned, student-driven wire service.

NEW LEADERSHIP

Blair had an impressive resume: reporting and copy editing positions at The Diamondback, an internship at The Washington Post, reporting at Capital News Service.

Eager to boost that resume, Blair applied for The Diamondback’s editor in chief position — which is named in April — in the spring of 1996.

Dave Murray, the then-sports editor, seemed the obvious choice and the newsroom favorite, staff members said.

Maryland Media Inc., a non-profit company separate from the university that oversees The Diamondback, Mitzpeh, Eclipse and the Terrapin yearbook, chooses the editor. The company consists of lay board members, along with alumni. Christopher Callahan, then an associate dean in the journalism college who helped Blair land high-profile internships, strongly advocated for Blair for the position, according to a 2004 Baltimore Sun article.

The board elected The Diamondback’s former reporter, and staff members were furious. Murray had put in his time. How could Blair possibly be qualified when he didn’t have any leadership or managing experience?

So the editors convened in the middle of the night at Plato’s Diner on Route 1. They would go on strike, they said, until the board came to its senses.

The editors tried to tell the board why Blair couldn’t be in charge. All they heard in response, Newman said, was that they couldn’t handle the success of a black man.

“We’re not racist,” the editors told the board. “This has nothing to do with the fact that he’s black.”

It didn’t matter what they said. Blair would begin helming the newspaper in a few weeks.

MISHANDLING MONEY

Maybe working on the paper was frustrating, but at least they were making the money they needed, reporters and editors thought. That could keep them going.

But when they went to pick up their paychecks, they found far smaller payments than in past years. They had no idea where the money was going, but suspected Blair was paying his assistant — a friend named Susan Freitag who had no prior experience on The Diamondback — a large portion of the honoraria.

The editor in chief is given a sum of money — an honorarium — to pay his or her staff. Reporters were paid a standard rate for every article they wrote, and editors were paid per shift. Staff members would submit a list of how much they worked to the editor in chief.

In past years, the managing editor looked over the pay amounts as an independent auditor of sorts. But Blair only allowed Freitag — whom no one else on staff really knew — to look at them, Madigan said.

There was a general lack of organization under Blair’s tenure, staff members said. It wasn’t clear who should read and edit stories, who should design pages and when and how the pages should be sent to the printer.

And while many editors came in at 5 p.m. and stayed until the paper was sent to the printer at about 1 a.m., Blair broke editor in chief protocol and rarely stayed the whole night.

But the editors grew accustomed to his consistent absence. It only became intolerable when that lack of organization began affecting their personal and financial lives, they said.

Blair’s leadership was difficult enough to work under, many staff members thought. The smaller paychecks — which they often needed to help with tuition or other expenses — were inexcusable.

Both managing editors and two news editors left after Blair’s first semester as editor in chief, Newman said.

After dedicating time as a sports writer and editor in his early college years, Madigan took on fewer responsibilities at the paper during Blair’s tenure. Staff members knew Madigan was one of the few people Blair respected, so they asked Madigan to talk to Blair about the way he was handling the honoraria during the second semester.

Madigan sat in the editor’s office with Blair for 30 minutes, requesting he see exactly how much people were being paid and how Blair distributed the honoraria. But it was more like the same five-minute conversation six times, Madigan recalled.

“Look, Jayson, you have people that are upset. It sounds like they have reason to be upset,” Madigan remembered telling him. “It would really help if I could come out of this room and have them believe me that everything is on the up and up. It would really help if I could see the numbers so I could do that.”

Blair closed his eyes and shook his head, pursing his lips, Madigan said. It was as if Blair wished he could help but simply couldn’t.

“You know, Tom, I just don’t, don’t think I could do that,” Blair responded.

When Madigan walked back into the newsroom, staff members looked at him hoping for some relief.

“No,” Madigan told them. “I didn’t see the numbers.”

SUCKING IT UP

They were going to miss their deadline — again. It was 3 a.m. in the newsroom, days before spring break, and staff members still had plenty of work left on a special insert.

The server crashed. It wasn’t unusual, Newman said, but they needed access to the production office across the hall from the newsroom to send the pages to the printer. Blair was the only one, other than the production manager, with the key.

They paged him nonstop and called his dorm room for an hour, Newman said. They wondered, where the hell was he? He couldn’t even pick up his phone?

Clearly aware they couldn’t finish the insert in time, livid staffers returned a few hours later when the business managers could unlock the doors.

While Newman — the then-managing editor — was finishing up the supplement the following morning, a friend asked her if she had heard what happened to Blair.

“His roommate left the gas stove on, and he passed out and almost died,” Newman’s friend told her. “If his roommate hadn’t woken him up, he would’ve died.”

Blair showed up to the editors’ meeting at 5 p.m. that day, as he usually did, with a raspy voice that “got just a little less raspy” as the meeting wore on, Newman said. He told Newman he needed to go home to rest.

Staff members, who didn’t believe the story, found it more amusing than anything else. They recounted the story for each other in emails after Blair left the newsroom that day.

“Get a load of this,” they wrote to each other.

But one staff member was almost certain there weren’t gas stoves in the dorm rooms, so Newman called the Department of Resident Life and asked. There were only electric stoves on the campus, she learned.

Blair’s sloppiness carried over into his course work, said Chris Hanson, a journalism professor whom Blair helped hire as a member of the search committee, as he turned in assignments late and his grades slipped. But faculty members didn’t see his carelessness to the extent Diamondback editors did.

“The biggest single lesson of this is that it was Jayson’s fellow students who were onto him first,” Stepp said. “He was a smart and capable young man who was perhaps a little immature. That’s true of so many students.”

While faculty may not have seen the extent of Blair’s shortcomings, the editors decided they had reached their breaking point. A couple of days after Blair’s gas stove story, they met at Plato’s Diner on Route 1 to craft a plan of action.

“What are we going to do?” they asked one another. “Are we just going to suck it up and wait until he leaves in May, or are we going to go to the board?”

They decided to hold back. After all, they had made it this far. How much worse could the next couple of months get?

AN EARLY EXIT

Donald Gene Castleberry, a junior at the university, was found dead in the Delta Tau Delta fraternity house in April 1997. Local media outlets were covering the story, so Blair jumped at the opportunity to lead the coverage.

Rumors circulated that Castleberry died from a drug overdose. There weren’t any autopsy reports yet, but Blair decided the rumors were enough to warrant dispatching a reporter, Alan Sachs, to write a story, which ran on April 8, 1997, Newman said. But printing a story solely based on rumors violates basic journalistic standards.

“The cause of junior English major Donald Gene Castleberry’s death is still a mystery,” the lead of the front-page story read, “but many campus students have come to their own conclusions about the incident.” The story included student quotes that speculated he died from a cocaine overdose.

An autopsy released the following day, however, found that drugs were not responsible for Castleberry’s death. The campus community was outraged, Newman said, and numerous readers wrote letters lambasting The Diamondback.

But Blair, who edited the story, didn’t stick around to deal with readers’ complaints. Closely following the story, Blair announced his resignation without explanation, but still wrote two follow-up stories with Sachs. He’d intern at The Boston Globe that summer, and go on to The New York Times the following summer, before eventually being hired without graduating from the university.

Typically, The Diamondback’s editor in chief-elect is named in early April and takes over about three or four weeks later. But Newman, the only applicant that year, had to take over the night she was named.

Hoping to squelch complaints after Sachs egregiously reported Castleberry’s death, Newman wrote a column apologizing for the rumor-based story.

But it was a small price to pay for Blair leaving.

“I was glad for him to go because it meant we could define a process,” Newman said. “We had a very ill-defined process because it changed whether or not he was there or whether or not he decided to be involved with something.”

Editors and former staff members planned a party that night to celebrate an end to Blair’s term. His terrible reign was finally over, they thought.

For some reason, Newman said, Blair decided to stay until the paper was sent to the printer that night — a rare occurrence.

“Just go so we can have our freaking party,” Newman thought.

At about 1 a.m., after the paper was sent to the printer, Blair finally left. “Lyin’ Eyes” came on minutes later, and everyone cheerfully sang along together.

“You can’t hide your lyin’ eyes.”

newsumdbk@gmail.com