In a way, it’s fitting that She Kills Monsters will become the first-ever virtual play from the University of Maryland’s theatre, dance and performance studies school. Most of it takes place in an alternate reality, and the storyline centers on grief — which is increasingly relatable during the coronavirus pandemic, says Miranda Hall, the show’s assistant director.

“Many of us are grieving — we’re grieving our old lives, we’re grieving school and work, we’re grieving family members that we miss,” Hall said. “But this play focuses so much on healing, and I think that’s what people really need right now.”

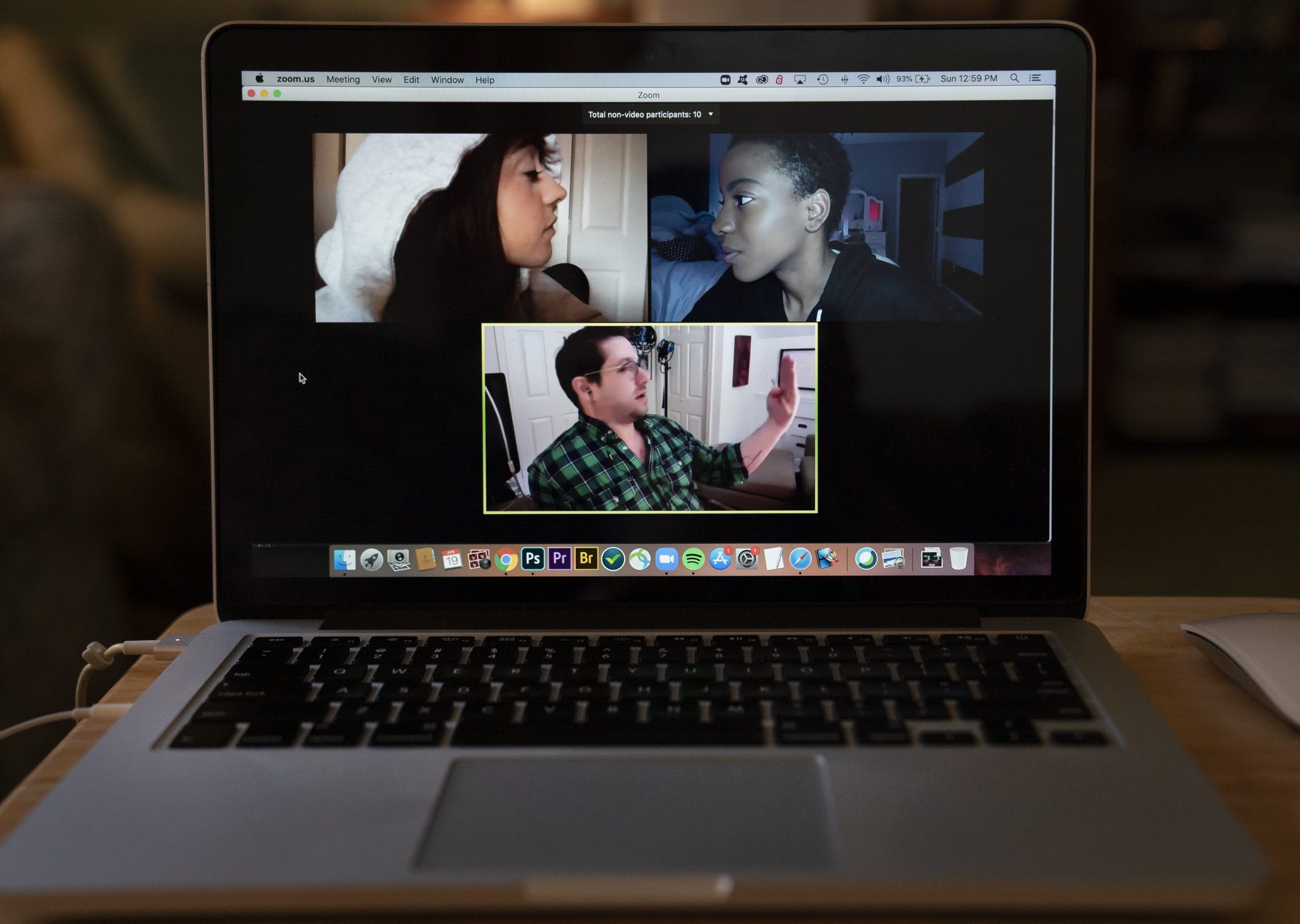

Next Thursday, the cast will make history, becoming the first actors to livestream playwright Qui Nguyen’s 2011 play over Zoom. In the process, they’ll be testing the limits of multimedia theater, setting an example for an industry so heavily impacted by the pandemic.

Last year, faculty chose Nguyen’s play for the spring performance. Those plans were interrupted, however, when the university announced in March that all classes would be online for the rest of the semester.

In mid-March, Jared Mezzocchi, the play’s co-director, brought up the idea of producing the play virtually.

Mezzocchi, a professor in the school’s graduate design program, had been disappointed with the plans theater companies implemented as a result of the virus: actors performing in front of empty seats or substituting their productions for livestreamed script readings — ideas he compared to a eulogy.

“Do we have to be giving eulogies all the time about the thing that we can’t do anymore?” Mezzocchi asked. “Instead, how do we say: We can do something with this, we just need to look at it a little differently?”

Taking the stage home

She Kills Monsters follows the story of Agnes Evans, who discovers a Dungeons & Dragons module her younger sister wrote just before her death, leading Agnes on a journey that brings her even closer to her late sister.

At first, Jasmine Mitchell, who stars as Agnes, had a lot of questions. She was worried about how the show would translate to an online platform, as the play features different settings, elaborate costumes and choreographed fight scenes.

And about a week and a half ago, Nguyen had the answers. He sent over an adapted version of the original 2011 script that would better suit the play’s new setting.

[Read more: UMD performance, arts students adapt to online learning — without a stage or dance studio]

Moving the production online and attempting to recreate a live theater experience required creativity. The cast and crew accepted that the experience wouldn’t be exactly the same as a live show. Still, they remained committed to keeping the audience engaged, even if it has to be through a computer screen — a problem that Lisa Nathans attempted to solve.

Nathans, a theatre professor and the show’s co-director, previously taught camera acting in Los Angeles. She knew there would be a learning curve for the student actors, who were used to worrying about projecting their voices or accentuating their gestures on stage.

Nathans and the cast devised a number system for different camera angles to make the audience feel as if they were within feet of the performers. A low number designates a position closer to the laptop camera — used for intimate scenes — while higher numbers are for positions farther away and could be used during fight scenes. Alone in their rooms, actors will have to adjust these angles on their own as the play progresses.

“When it’s a laptop screen — and you’re physically alone but virtually sharing space with other people — you have to learn,” said Mitchell, a senior theatre major.

Killing monsters, virtually

There was also a need to bring a “Brady Bunch” element to the production, Nathans said — a way to create cohesion among the individual actors’ Zoom squares so as to appear as if they’re all in the same setting.

Spotlights turned into desk lamps; the set design, which had been six months in the making back at school, turned into different Zoom backgrounds; special effects turned into create-your-own Snapchat filters, and costume fittings became a “What’s in my closet?” video call.

Getting to play with virtual tools that wouldn’t have been available in a live setting became an advantage, Nathans said.

“There are elements of fantasy and magic and battle, this otherworldliness, that we can really dive into and explore virtually, that also a live theater doesn’t allow for in the same way,” Nathans said.

However, there are still risks that come with performing a play on an app originally developed for business meetings — drawbacks that a live performance could exacerbate.

A cast member’s Wi-Fi could go out, or a laptop could lose battery in the middle of a monologue. And though these possibilities increase Mitchell’s nerves, she said there are certain safeguards in place — just as there would be an understudy for a stage performance, there’s an understudy available in the case of weak Wi-Fi.

But performing live is one of the most important elements of theater, Mezzocchi said, and one that both he and Nathans were eager to preserve.

“Ultimately, why theater feels really good is because it’s a ritual in which people come together and know that it could go wrong, but it doesn’t,” Mezzocchi said. “And when it does, everybody celebrates each other and holds each other up.”

[Read more: Zoom juggling, debates and book clubs: A look at how UMD orgs are connecting amid COVID-19]

An uncertain future

Ever since the play transitioned to Zoom, there’s been a sense among its faculty directors that the “research project” they’ve taken on transcends this single performance.

“We’ll pause and remind ourselves that we’re the only ones in the country doing it and saying yes to it,” Mezzocchi said. “That is a bit of a burden at times … but a good reminder that we’re way out front trying to explore this. And that’s exciting.”

In some aspects, it’s become a quest to keep the theater industry alive at a time when its future is uncertain. Nationwide, theaters have been forced to shut down indefinitely in the midst of the pandemic. And the large, packed-in gatherings that live theater requires may not be permitted even after other industries reopen, Nathans said.

Turning to digital platforms and reimagining shows for an online performance could be a temporary way to bring new life into traditional shows, Mezzocchi said. And though it’s uncertain whether the Zoom shows will continue beyond this performance, the cast and crew are determined to be at the forefront of the virtual shift — even if they can’t be together to celebrate it.

“One of the lines in the script that we’ve been using as a guide-post is ‘And this made her happy.’ That’s been really important to the process — at the end of the day, are we all still having fun?” Nathans said. “The show must go on. And that’s what we’re figuring out how to do.”