About 10 minutes before midnight on March 27, Simon Polson left his house in Sydney, Australia, carrying about five grocery bags.

At that time, Australia was in its 15th day of lockdown, and people could only leave their homes for a few specific reasons. If the police stopped Polson, he had an excuse at the ready: He was on his way to the 24-hour grocery store.

But Polson was actually headed to a friend’s office, somewhere he felt confident the internet connection wouldn’t fail. Three hours later, he had earned his doctoral degree from the University of Maryland’s music school.

Polson is one of about 160 graduate students at this university who have already defended their dissertations online — an achievement that marks the culmination of years spent working toward their degree. The presentation is usually given in person, but due to the coronavirus pandemic, this university’s Graduate Council voted in March to allow remote dissertation and thesis defenses.

The graduate school has received “tremendously positive” responses from the remote defenses, said Scott Roberts, the school’s assistant dean. The graduate school provided guidance and resources for remote defenses, publishing guidelines on their website for both advisers and students.

“We hear it’s gone really well, and we really appreciate the ways in which students and faculty have kind of stepped up to the challenge and made it work,” he said.

Though Polson returned to Australia last May, he had planned on traveling back to Maryland to defend his dissertation. He was looking forward to seeing his friends again and shaking his adviser’s hand at the end. But the weekend before his flight, Australia closed its borders.

[Read more:UMD community reflects on celebrating Passover apart from family and friends]

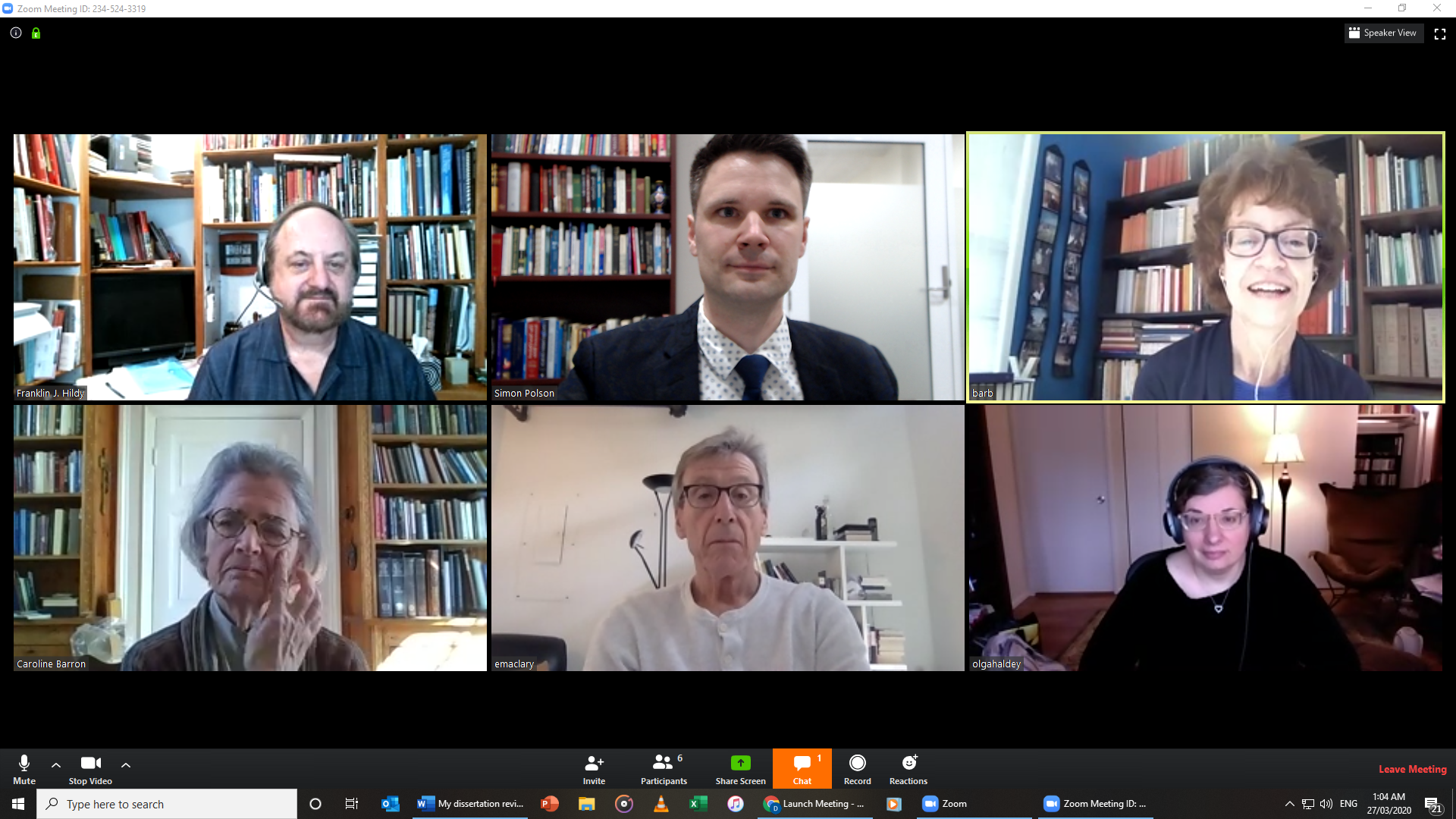

So instead, across time zones, five examiners from this university and one based in London logged into Zoom to hear Polson speak.

The defense was strange and exhausting, he said. He even set about 10 glasses of water in front of him to drink whenever he felt too tired.

“I do remember at one point, I almost wanted to ask if it would be okay if I stood up and went and did some star jumps or something,” he said.

But there were some advantages to the online approach, Polson said. People who would have otherwise been unable to watch his presentation — friends in Australia and the U.S. and his family members — were able to tune in. And while he didn’t get to have the party he would have had on campus, he did meet with friends on Zoom to celebrate later. Normally, an adviser told him, they would’ve popped a bottle of champagne for him.

Nooruddin Shah, another doctoral student who defended remotely, prepared for the worst. He sent his presentation to his adviser, in case his connection failed and he needed to call in. He also asked his wife to keep the kids in their room, so they wouldn’t burst in on the presentation.

But the defense went a lot better than he was expecting, Shah said. Even though a committee member was momentarily disconnected, the rest went smoothly.

“I was very satisfied with my own performance as well,” he said. “I will give that credit to my chair and committee members who made that environment easy for me.”

After the defense was over and the decision was announced, Shah’s family joined him. He called his parents and family members, and before he could tell them the good news — that he had earned his doctorate in international education policy — his daughter blurted it out.

“My daddy has passed the exams,” she said to her grandfather, excited.

Later, the four of them celebrated with a feast, with dishes typical to the mountain areas of Pakistan, Shah’s home country. However, he said he missed the personal aspect of in-person defenses.

“We share food and we celebrate,” Shah said. “You can see each other’s expressions. You can tell them, even better when it’s face to face, and you can understand better the questions asked by the committee.”

[Read more: Yoga, music, haircuts: UMD alum’s “Impromptu Streams” page has more than 1,000 members]

Another student, Les Gray, expressed disappointment that they endured four years of arduous work in the theatre and performance studies doctoral program only to have it culminate in an online defense. This felt especially disheartening as an underrepresented minority student, they said.

“There’s a lot of emotional energy and labor that gets put into this degree of work,” they said. “Especially if you are underrepresented, regardless of how much support you’re getting, you’re still gonna struggle … the idea is that your struggle leads to less struggling for the people that come after you.”

Gray said the program took a severe toll on their mental health, but they were looking forward to the little silver linings. They pictured waiting outside the room with their friends, waiting for the committee to make a decision. Then, someone would come out and say, “Come in, Dr. Gray.”

Instead, as the committee deliberated, Gray waited alone.

“I felt like I was robbed of those experiences,” Gray said.

The day of the defense, they were anxious and tired. While having to defend in-person would have been just as exhausting, at least they wouldn’t have had to prepare a room to present their dissertation. If they had defended on campus, they would have just had to walk into the room they had booked with their computer and a notebook.

Instead, Gray defended in their apartment. They struggled to find a nice setting for the presentation, since every sitting area is located against a window. Around 20 minutes before the presentation, they were still fixing the lighting. It felt uncomfortable to have a whole committee in their home, even virtually.

“Part of my dissertation is about the idea of home,” they said. “I’m very particular about who I invite into my home.”

While the defense went well, Gray said they hope the university does not think it is a viable option for everyone.

“It’s not a uniform process,” they said. “If you’re living in a space that is not safe or is really loud … there’s not a lot of options as far as changing your environment.”

But Amanda Woodward, a doctoral student in this university’s psychology department, said she likes the idea of presenting a remote defense as an option, even if the circumstances were not ideal. It was fun to defend her dissertation to an audience of about 40 of her family and friends.

“I’ve talked to my family about my research and I’ve talked to my friends who are in grad school about it,” she said. “But this was the first time that they really saw what my research looked like.”

According to the modified policy on remote defenses, normal rules for the examination should apply once in-person instruction resumes. While the graduate school hasn’t discussed yet whether remote defenses will remain a reality in the future semesters, Roberts said this pandemic is going to force the graduate school to rethink many of its current practices.

“I’m fascinated by how this is all gonna play out,” he said. “We’re all going to look back over this phase, and it’s going to be a watershed moment for how many things have completely changed for better and worse in the way that we do things.”

Over 10,000 miles away, Polson echoed Roberts’ remarks.

“I think in sort of five or six years’ time … it will be quite special to think that there was kind of just one year where [there were] those of us who finished our doctorates or people finishing high school at the moment,” he said. “It is a sort of a special group of people that had such a different experience to everyone else.”